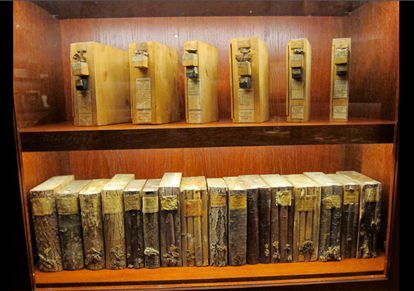

Mark Dion's "Xylotheque (Wood Library)", Ottoneum, Museum of Natural History Kassel. documenta 13, 2012. (cc Stella Veciana)

Presentation of the "Federal-State Key Issues Paper on the research museums of the Leibniz Association", Museum of Natural History Berlin, 12th of December 2012.

(cc Stella Veciana)

|

Generating and exhibiting "scientific objects": From the „Cabinets of Curiosity“ to the Research Museums

The "Xylotheque" (Wood Library) by Carl Schildbach dates from the 18th Century, and is located in the Kassel Natural History Museum. It consists of 530 "books". Each book is made from the wood of a native tree species. The bark of the trees is used for the spines, and the plant parts, dried or reproduced in wax, are "exhibited" in the interior of the books.

Joachim Heinrich Campe, who was a contemporary of Schildbach, gives an interesting description of him: "This to me remarkable man has neither education nor scholarly knowledge of any kind, and yet he has acquired skills and knowledge in natural history and the theory of nature by his own diligence and without any aid, that would bring honour to any scholar. He is a born artist, but as far as I know – he has never learned art from others, nor worked professionally. Everything his vivid imagination shows to him, he is able to represent artistically." According to this source, this is not a natural history scholar, but an interested self-taught man with artistic skills, who has found his way into the "ivory tower" of a scientific museum. What prerequisites and legitimacy are required of citizens without academic title, for them to be accepted as citizen scientists capable of generating and publishing their findings?

In 2012, at the documenta 13, Mark Dion (*1961, New Bedford, Mass.. USA) presents Schildbachs’ “Wood Library” within a hexagonal oak cabinet. By using oak as his material he refers to the ecological urban intervention "7000 Oaks" by Beuys, which was presented during documenta 7 and 8 (1982 - 1987). Furthermore, the cabinet as the form of presentation refers to the cabinet of curiosities, the historical antecedent of the natural history museum. With this cabinet, Dion presents the research object "tree" in a new light. He also adds a further six books from other continents to the collection. With his project, Dion questions the classification systems of science museum collections. What kind of scientific classification systems, models of archiving, and presentation architectures are needed for a contemporary participative science communication? How can we all take part in shaping to our collective memory?

The cabinet of curiosities as "accumulated collections of scientific objects", in the 19th Century develops into the systematized knowledge archives of natural history collections with increasing scientific claim. Now, at the beginning of the 21st Century, the model of the "research museum" is being discussed. On the 12th of December 2012, in the Natural History Museum Berlin, a parliamentary evening on the theme "Museums as bridges from research to education" was organized. The director of the museum, Dr. Johannes Vogel, presented jointly with Thomas Rachel (Parliamentary State Secretary BMBF), Dr. Karl-Ulrich Mayer (President of Leibniz-Gemeinschaft), Dr. Volker Rodekamp (President of German Museums Association) und Dr. Wiebke Ahrndt (Vice-president of German Museums Association) the "Federal-State Key Issues Paper on the research museums of the Leibniz Association (WGL)”. It explains the science policy framework for future scientific work in the museums of the WGL, and how it will contribute "to strengthen Germany as a centre for education and science”. The following are considered the four most relevant areas of guidelines for the development of future fields of action for the research museums of the Leibniz Association:

- The Research Museums of the Leibniz Association are primary places of Science and Research

- Museum collections as research infrastructure for scientists from around the world.

- Museums as bridges from research to education.

- Interactions of different research areas and synergies between the research museums.

The third point relates to the areas of science communication, (specialized) knowledge transfer, knowledge dissemination, "critical dialogue" and consultancy regarding socially relevant issues. The following fields of activity were presented under this heading:

- The participation of research museums in the German program "science year"

- Public involvement of the research museums in the theme of "Innovation and Technology Foresight"

- The development of measures to attract young people and “educationally deprived strata of society“

- Linking the regional roots of research museums with regional educational initiatives

- The specific contribution of museums on "Research, Science and Technology as cultural heritage"

- Strengthening the sustainability of knowledge transfer: Long-term and wide availability of knowledge

- Trade-related knowledge transfer

- New forms of knowledge

- Permanent exhibitions as “windows to research”

- Research museums set their own topics for the work with public relations.

Dr. Volker Rodekamp, President of the German Museums Association, emphasized in his speech that Germany no longer needs (new) museums, but rather that the already existing (old) museums, need to become more modern, more efficient: "with standards that we develop on our own, with needs that we formulate ourselves, with criteria of excellence that make the scientific quality measurable, with an increasing significance that will give us more political weight, with a intermediation capable of moving people, with a target group knowledge that achieves a growing effect"... All these standards would, of course, need the appropriate funding and infrastructure.

What would a more “contemporary” scientific knowledge communication (in museums and art institutions) look like? How could the citizens be more actively involved in the curatorial work instead of just being analysed as target groups by market research agencies? The challenging task of "translating" between science and society also raises the question of participation within science and the art system: the question of the participation of formerly untrained "non-scholars", which we may now call "the experts of the everyday". What should the relevant guidelines and the future fields of activity of “research museums” look like? What claims do the RESEARCH ARTS community have towards a natural history museum, a research museum, or towards cultural institutions in general? What should the RESEARCH ARTS community demand of science policy?

comment |