Workshop Synergy: Interdisciplinary Practice and Theory, During the Synergy Workshop Simon Penny presented the draft of an Interdisciplinary protocol that contains his long expierence developing the Arts, Computation and Engineering program ACE at the University of California Irvine (UCI). Simon Penny was founding Director of the ACE Program. Hangar, Barcelona. 28th to 30th of June. (Photos: Stella Veciana).

The Arts, Computation and Engineering program ACE (2003 - 2009) at the University of California Irvine (UCI). (Banner: ACE).

ACE student Eric Mesple working on his kinetic sculpture using ferromagnetic fluid, 2009. (Photo: Simon Penny).

Two female students in the Welding bay - in Penny's class - Sewing for Boys, welding for Girls. 2008. (Photo: Simon Penny).

Mark Roland, ACE Graduate. Gravitableis a furniture platform for engaging people in socialization and reflection through networked information, 2008.

Pearl Ho, ACE Graduate. FDA (Food Diagnostic Activism) at Home is a technology for detecting the presence of pesticides in food, 2007.

ACE student Marvin Park playing Go on Shan Jiang's Goscape (instrumented Go board producing musical accompaniment to game status), 2007. (Photo: Simon Penny).

Simon Penny, Founding Director of the ACE Program. Reconstruction of Petit Mal (1993-95), Transmediale Berlin 2006. (Photo: Simon Penny).

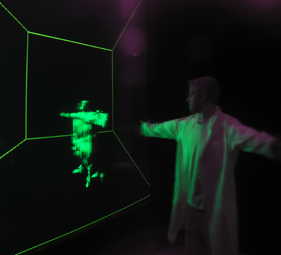

Simon Penny, Body Electric is an immersive interactive environment in colaboration with Neuro-ethologist Malcolm McIver of the Center for Neuromorphic Systems Engineering, CalTech, 2003. (Photo: Simon Penny).

Simon Penny, ACE T-shirt designs.

|

What do we mean with interdisciplinarity and why do we care?

Simon Penny

»In order to do interdisciplinary work, it is not enough to take a ‘subject' (a theme) and to arrange two or three sciences around it. Interdisciplinary study consists of creating a new object, which belongs to no one.« Roland Barthes[1]

»The main point to realize is that all knowledge presents itself within a conceptual framework adapted to account for previous experience and that any such frame may prove too narrow to comprehend new experiences.« Neils Bohr[2]

Introduction

Interdisciplinarity is a theme which dances around pedagogy and research, often in vogue, and lauded as a wellspring of innovation. Regrettably, just as often, the term is leveraged in initiatives which employ the term in limited or even counterproductive ways. The first question that must be asked of any such enterprise is why is the term being deployed and to what ends. The first observation that must be made is that interdisciplinarity is a symptom of disciplines. The idea that disciplines and disciplinary boundaries are somehow pure or stable and divide up the pie of human knowledge in ordered and rational ways for all time is of course nonsense. Disciplines are historically contingent, they rise and fall and change and adapt. Disciplines embrace fractious factions within them, and are defined in heterogenous and incompatible ways, by subject matter, by methodology, by philosophical orientation. Disciplines overlap, they share content, they share methods. The dotted lines that ostensibly separate disciplines are blurred and overlap. New disciplines come into existence, usually through the process of interdisciplinary formations. They usually come into existence due to a principled recognition that existing formation are not adequate to the task at hand. The emergence of fields such as computer science and women’s studies are examples of the recent past. Media Arts and sustainability are more contemporary cases.

My experience in this field is largely in the realm of media arts. By 2001 I had spent over a decade involved in digital media art as a practitioner, a theorist, a teacher and an administrator. Over that period it had become clear to me that the field was so profoundly hybrid that neither an education based in the arts; nor one based in computer science and engineering; nor one based in media studies and critical theory; were sufficient to prepare a young practitioner to make well informed and well formed work. In 2001, I was offered an interdisciplinary position at University of California Irvine (UCI) jointly in Electrical and Computer Engineering and in Studio Art. I proposed to establish an interdisciplinary graduate program in media art theory and production. After two years of planning, proposals, and approvals, the development of premises and hiring of faculty and staff, the program opened as a masters program in fall of 2003. The program was called ACE, which represented the three schools which supported it – Arts, Computation and Engineering. In what follows, I will recount some of the lessons I learned in attempting to realize radical interdisciplinary pedagogy.[3]

The emergence of media-arts and digital cultural practices has provided a highly charged context for the development of interdisciplinary pedagogy, combining as it does, practices and traditions from historically, culturally and theoretically wildly divergent disciplines. This paper addresses aspects of effective interdisciplinary educational process, attending to questions of pedagogy, theory and institutional pragmatics. There is ongoing discussion about the relative merits of interdisciplinarity, multidisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity, even antidisciplinarity.[4] I am here not so concerned to debate the merits of these approaches as to discuss what happens in practice when, in response to perceived need in pedagogy or research, an attempt is made to combine often divergent disciplines. Therefore (with apologies) I employ the term ‘interdisciplinary’ loosely.

In my analysis, the key components of the ACE project were: deep technical training and understanding; deep training in artmaking and cultural practice; deep theoretical and historical contexualisation, and an open and rigorous interdisciplinary context which maximally facilitates the negotiation of these often divergent ways of thinking and making. Some educational programs seemed to embrace any two of these three conditions, but each pairing revealed the substantial deficit of the third.

A further task was a key part of ACE, and that was to learn build a relationship between these three components. This is a central task of interdisciplinarity – to find some way of negotiating a discourse among ideas and methods and phenomena which are fundamentally incompatible and heterogenous. Graduation in ACE required a realisation of this process – students were expected to present in public a fully functional project, along with a written thesis which positioned the work historically and in terms of contemporary culture, and described its development process and its technical design. Along with this the students took substantial course-work. It was a rigorous program, resembling more an accelerated PhD than a conventional masters degree.

In building such interdisciplinary practice in the context of a campus, one abruptly confronts the discontinuity between rapidly changing fluidity of the contemporary moment and the relative stasis of institutionalised disciplines which have an investment in maintaining their identity in the face of such change. Implicit in the project then, is not simply the development of a context for deep interdisciplinary invention, but the formation of practitioners who are neither artists nor engineers, or who are equal parts both. In either case, this formation confounds the disciplines and creates a vacuum of institutional context which has resounding implications for the survival and flourishing of such initiatives and their practitioners.

The great liberty of such initiatives is the opportunity to shape a new practice outside the constraints of established structures. The price of freedom being (as it is) eternal vigilance, there is danger in such initiatives, and to those involved, in existing outside established structures. The danger is to find oneself ‘off the map’, stranded in a ‘no man’s land’ unstructured by procedures which elsewhere have heuristically developed as a responses to needs over time. The required antidote to such all-too-common fates is attentive management which, like the attentive parent of a toddler, allows exploration but is there to catch her when she stumbles.

I suppose no such idealistic venture could ever exist without optimism, energy and naivety in large and roughly equal measures. In retrospect, this was true for me and for ACE. Virtually everything about ACE went against accepted procedures and the university culture. Like many campuses, UCI is structurally divided according to disciplines. At UCI, the divisions between schools are so significant as to substantially impede student movement beyond school boundaries. On an intellectual level, philosophical commitments, research practices, and marks of professional validation in one school were incomprehensible in another. In terms of administrative procedures, differences were equally stark.

Early History

Established in early 2003, the Arts Computation Engineering graduate program at the University of California, Irvine was designed around the notion that only a broad and thorough-going interdisciplinarity would meet the needs of a program purporting to equip practitioners in the merging fields of media arts and digital cultural practices.[5] The fundamental premise of the ACE program was, and is, that a pedagogical program adequate to the emergence of a new range of hybrid techno-cultural practices must not simply provide skills and knowledge, but must provide a context in which to identify and interrogate the structuring characteristics of these new practices. Based on experience of practice and pedagogy in the preceding decade, it was recognised that to apply traditional methods of one discipline to new tools emerging from a very different discipline creates a Pandora’s box of theoretical conflicts which would continue to, as it were, rip through superficial veneers of rhetoric’s of convergence. To avoid this, and to place the practice on firmer theoretical ground - to, in fact, take part in the creation of that ground - a pedagogical program which could mix knowledge and practices of traditionally separate disciplines was required. Furthermore, such a program must be constantly attentive to the schisms and discontinuities which emerge when such practices are combined.

Such a program demands, then, a broad understanding of the way that social, cultural, historical, economic and technical aspects mesh together and evolve. Further, a deeper, historiographical and epistemological study is called for, in order to determine which existing disciplines are called upon as relevant; to understand the way that fundamental commitments shape the value-systems of these disciplines and; to draw upon historical precedents in order to construct a sense of historical continuity.[6] And lastly, when these various forces are thrown into the crucible of interdisciplinary negotiation, in the classroom and the lab, we must remain alert as to which reagents react violently - who has the protective clothing, and who wears the burns. This perhaps fanciful analogy, in my experience, captures the intensity of some collisions of disciplinary world-views.

The agenda of the program then was to take an intellectual high road, expressly to not provide narrow vocational training aimed at one or other of the digital arts industries (graphics, animation, gaming, web-design, etc); nor to harness media artists to the cart of applied technical research; but to train a cadre of thoughtful practitioners who would be well equipped to make significant and innovative interventions in the evolution of these practices and in this interdisciplinary space: to play a role in the development of critical digital cultural practices comparable to Philip Agre’s notion of critical technical practice in computer science.[7] The emphasis on technical and artistic practice and production is central – ACE does not aspire to train theorists of other peoples’ practice. The reconciliation of theory and practice is a central dimension of the interdisciplinarity of ACE. Indeed, the very separation of theory and practice is taken to be a problematic legacy of an academic Cartesianism of questionable validity and relevance.

Deep Interdisciplinarity

As human culture is immersed in a historical process, so knowledge is a moving target - new realms present themselves as a result of theoretical, social or technological change. Universities and institutions of higher learning have generally recognised a responsibility to foster exploration into such areas. Yet these interests are fundamentally at odds with the institutionalised nature of the larger organisations themselves. As disciplines form and elaborate, they necessarily build an administrative and institutional superstructure around themselves. As personal power and vested interests come into play, these structures crystallise, they become resistant to change, increasingly unable to adapt to new contexts. Yet new contexts continue to arise and the academy must accommodate and explore them or become moribund.

Interdisciplinarity has of late become a mantra of universities because, presumably, it has been noted that significant innovation originates form outside disciplines at least as often as it originates from within them. It would seem self-evident that this is because disciplines are inherently conservative. There are sound reasons for such institutionalisation, and the Marxist dream of the institutionalisation of permanent revolution seems intractable in long-term practice. If the entire institution cannot flow, then at least one hopes that there can be some flow around and between the immovable objects. Hence, one assumes, the general enthusiasm for interdisciplinarity as a middle way. It is where the action is, where the new knowledge is, and it is therefore where campuses with a commitment to research would presumably want to be.

Many things pass for interdisciplinarity. I distinguish between a more or less shallow instrumental mode, and what I call deep interdisciplinarity, which, I argue, while more challenging, offers potential general benefits in addition to the immediately identified pragmatic goals. An instrumental approach to interdisciplinarity sees such as necessary in order to bring together practitioners of relevant backgrounds to address complex projects which demonstrably cross disciplines, for example, the designing of a levee system to protect a city from floods while maintaining river ecology and navigability for cargo transport.

Interdisciplinarity can serve (at least) three functions. The first is the pragmatic, applied function I call ‘shallow’: the task at hand demands a range of expertise which exceeds disciplinary boundaries. The second is more abstract and is aimed at epistemological and ontological concerns I refer to as ‘deep’ : the elucidation and clarification of the structures and commitments of disciplines themselves and the relations between disciplines. Such consideration can in turn lead to a third function: the identification of new areas of research and practice. This third can arise out of the first, but without serious commitment to the second, it may founder on misunderstandings arising out of mismatches of technical jargon or, more deeply, incommensurabilities in the assumptions which ground disciplines.

There is a simplistic assumption abroad that to practice interdisciplinarity, one can simply drag the methodology or subject matter from an outlying discipline into ones own (with a click of the mouse, as it were). In its most cynical and unenlightened forms, such a process is inherently imperializing and retains an unreconstructed disciplinary hubris. It retains the master discourse status of the ‘home discipline’, and is thus unable to recognize that in the process of uprooting the products of the outlying discipline and bringing them ‘indoors’, they might in the process wither and die, transformed and reduced like bleached specimens preserved in formalin. In the worst cases, shallow interdisciplinarity resembles Viking-like academic pillaging and plundering raids, pulling exhibits from distant disciplines which, torn from discursive context, change or lose their meaning in the process. To maintain a conception of interdisciplinarity in which one's own discipline occupies a central position while others are arrayed on a periphery is a form of hubris which robs interdisciplinary inquiry of its potential.

Hubris and Humility

The recognition that the specialist expertise of ones own discipline is necessary but not sufficient to a certain task can result in more or less courageous responses. The less courageous is to retreat into the safe world of ones discipline and assert the sufficiency of its expertise. The more courageous response it is accept that it will be necessary to engage with others whose expertise is different from, often incompatible with or even incommensurable with ones own. When such a realization is carried forward, one confronts an ontological chasm, which, when considers, can throw light upon, not only the differences between disciplines, but on uninterrogated assumptions within ones own discipline.

These ontological differences can concern, for instance, fundamental motivations and justifications for working, methodologies and research processes, and ultimately, question assertions regarding knowledge and truth. Such realizations relativise discipline-based realites. As such they reveal that disciplines are cultures and that disciplinary partisans come, with or without full awareness, to share in a disciplinary world view which validates certain kinds of practices and not others, affirms certain ways in which the world is understood to be and renders others incomprehensible or invisible. For instance, while in some disciplines the notion of emergence even the notion of supervenient causation are well accepted, it other disciplines where reductivist methods are considered fundamental, emergence is regarded as a mysterious and mystical notion which cannot be thought within the disciplinary terms of reference.

All things must pass

The ACE program was terminated in 2009 and the last students graduated in 2011. This was due, ostensibly and immediately, to the financial crisis which gripped the university, state and nation, but I suspect its condition as monstrous with respect the campus culture would have caused its demise sooner or later. The period of these radically interdisciplinary programs in media arts seems globally to be on the wane. This is not surprising. All disciplines begin as interdisciplinary initiatives, driven by felt contemporary needs – as noted: computer science, women’s studies, biomedical engineering (etc) are no different. Such initiatives often follow a familiar pattern of drift towards institutionalisation. In the (so called) media arts, another factor of technosocial development is at play. In the early days of digital media – the late 80s and early 90s – the technology was in a primitive and research phase. Its potential was exciting but unclear. As a result it attracted a population of independent free thinkers and visionaries, among them many artists. The community was radically interdisciplinary. Misconceptions and misunderstandings were rife as reference points and criteria were hammered out.

In no small measure, the media art community prototyped modalities and developed technologies and generally did experimental work in these new forms. And as a result, new practices and new genres formed. As these ideas came into more general parlance, a different kind of creative mind saw in them potential commercial products. In this way, the jointly held intellectual property in the media art world drifted into the commercial world, providing the basis for web media, games, apps and other aspects of the diverse new market in digital commodities. The transition of machine vision based embodied interaction, from experimental artworks by Kreuger, Rokeby and others, to the Wii and the Kinect, via the Canadian Mandala system of the mid 90s, the SONY EyeToy and other transitional products, is evidence enough. But nothing indicates this shift as clearly as the sales on Grand theft Auto 5, which grossed 800 million dollars in the first day of its release (Sept 18, 2013).

It may well be that the interdisciplinary period of media arts is over, as its practices have moved into increasingly commercialized contexts and established genres, and because of this, the educational process is increasingly professionalised. Today there is a career path in the design of intelligent agents (non-player characters or NPCs) in online games. Not much more than a decade ago, such things had only just transitioned from be a futuristic idea to being a cutting edge research topic. But the lessons learned in such intiativaes as the ACE program are relevant to any knowledge enterprise which traces a path across and between disciplines.

© Simon Penny, 2013

↑ 1. Barthes, Roland. The Rustle of Language. Trans. Richard Howard. University of California Press: Berkeley. 1972. Page72. (Thanks to Josef Nguyen for this quote)

↑ 2. quoted in John Honner: The Description of Nature: Neils Bohr and the Philosophy of Quantum Physics. Oxford University Press 1987. pg 102

↑ 3. The history if the ACE progam is recorded in more detail in my paper Rigorous Interdisciplinary Pedagogy - five years of ACE. (Published in Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies SAGE Publications, Jan 2009). Some of the material here is adapted from that source.

↑ 4. for instance: Klein, J. T. Interdisciplinarity. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press. 1990. Mourad, R. P. Postmodern Interdisciplinarity. The Review of Higher Education - Volume 20, Number 2, Winter 1997, pp. 113-140. Turner, S. What are disciplines? And how is interdisciplinarity different? In P. Weingart & N. Stehr (Eds), Practicing interdisciplinarity Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. 2000. pp. 46-65.

Lattuca, L. Creating interdisciplinarity: Interdisciplinary research and teaching among college and university faculty. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press. 2001. Moran, J. Interdisciplinarity. Routledge, New Critical Idiom Series, 2002. Rossiter, N. Organized networks, transdisciplinarity, and new institutional forms. Intelligent Agent 6 (2). 2006

http://www.intelligentagent.com/archive/ Vol6_No2_transvergence_rossiter.htm. also at http://www.intelligentagent.com/archive/ia6_2_transvergence_rossiter_transdisciplinarity.pdf Augsburg, T. Becoming interdisciplinary: An introduction to interdisciplinary studies. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt. 2006. Szostak, R. How and why to teach interdisciplinary research practice. Journal of Research Practice, 3(2). 2007. http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/92/89. Youngblood, D. Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity, and bridging disciplines: A matter of process. Journal of Research Practice, 3(2). 2007. http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/104/101. Repko, A. Interdisciplinary research: Theory and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 2008.

↑ 5. Academic structures and terminology vary from school to school and from country to country. The terminology used here is US-centric. I regret any confusion this may cause to readers outside the US. In this paper, a ‘program’ means a formalised a plan of study which culminates in a degree, ‘faculty’ refers to individual academic employees, as opposed to ‘staff’ who are usually clerical or adminstrative.

↑ 6. See for instance, my ‘Bridging Two Cultures: towards a history of the artsit-inventor and the machine-artwork’, in Dieter Daniels / Barbara U. Schmidt (eds) Artists as Inventors / Inventors as Artists, Hatje Cantz, spring 2008. ISBN 978-3-7757-2153-0

↑ 7. see Agre, P, Computation and Human Experience (Cambridge University Press 1997)

|