"Is the Anthropocene legal?" Poster of the "Anthropocene-Project" at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 2013.

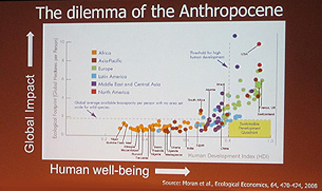

Will Steffen. Keynote "The Anthropocene. Where on Earth Are We Going?", HKW, 10th of January 2013.

The Anthropocene Project is an initiative of Haus der Kulturen der Welt in cooperation with the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Deutsches Museum, the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, Munich and the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, Potsdam.

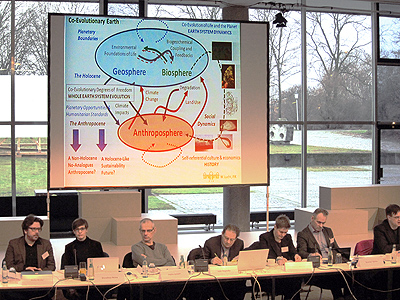

Introduction into the "Anthropocene-Project", Bernd Scherer (HKW) and Jürgen Renn (MOIWG). Introduction into the "Anthropocene-Project", Bernd Scherer (HKW) and Jürgen Renn (MOIWG).

"Open: Planetary Opportunities and Planetary Boundaries", Potsdam-Institut für Klimafolgenforschung (PIK).

Fifth Geneva Convention Projekt. "What is Violence After Nature?" Centre for Research Architecture, London. Fifth Geneva Convention Projekt. "What is Violence After Nature?" Centre for Research Architecture, London.

Prolog "Objects: Rock and a Floppy Disk", Lorraine Daston, Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte (MPIWG). Prolog "Objects: Rock and a Floppy Disk", Lorraine Daston, Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte (MPIWG).

"Metabolic Kitchen: Time to Cook", raumlaborberlin, Foyer HKW.

The "Anthropocene-Project. An Opening, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 10th of January 2013. (Photos: Stella Veciana).

The Kreuzberger Salon was founded by Miriam Wisel and Axel Schmidt in 2010 and in this monthly meeting a spectrum of topics relating to the relationship city >< countryside are discussed.

Exibition opening. "The Whole Earth. California und das Verschwinden des Aussen" within the frame of the "Anthropocene-Project", Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 25th of April 2013. (Photos: Stella Veciana).

|

"The Human in the Centre": Geologists Speculate About a ‘New Human Made Geological Epoch’, and the House of World Cultures About a New Research Agenda.

Stella Veciana

"Is the Anthropocene… legal," asks the colourful poster of the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (House of World Cultures). "What does this mean?", the passersby have probably asked themselves. The poster advertises the Anthropocene Project - a two-year project that opened on the 10th of January 2013 at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin. The scientifically controversial concept of the Anthropocene (Greek anthropos, "human ", and kainos, "new") refers to a period where "The Man-made New" is at the centre. According to the program brochure, the core thesis is: "Humanity forms nature." [5] As a consequence, we live in an epoch in which humans for centuries have made use of nature as a mere resource without recognizing that they are also equally parts of Earth System. On the following pages, we will reflect on what this discussion instigated by geology can bring our everyday life, and what the theory of the Anthropocene can contribute to a sustainable society.

The public awareness of geology is strongly tied to the image of the dinosaurs and the story of their sudden extinction. The artistic transmission of paleontological research in science-fiction film scenarios have undoubtedly stimulated the imagination and curiosity not only of countless children but also of many grown-ups. Stratigraphy, however, has hardly attracted public attention. It is the branch of geology which studies rock layers and sediments, and which date the geological processes and events of the past with a universal time scale. This lack of awareness, however, could change with a societal debate about the concept of the Anthropocene. Will human driven activities such as species extinction, the detonation of atomic bombs or nuclear accidents, have such an impact that they condense into an own clearly identifiable sediment layer? And if so, when did this process begin: with the industrial age, with the first nuclear detonation in 1945, or not at all? Could a time scale oriented on the past be useful in developing credible future models, given that such models will be needed in order to predict and prove if a future sediment layer has been formed by human activity?

Currently, the Sub-commission on Quaternary Stratigraphy is searching for evidence to prove the thesis of the Anthropocene. This evidence will be reviewed and approved in the last instance by the International Commission on Stratigraphy. We are still, and have been for about 11,000 years, in the Holocene, "The Entirely New" era (Greek holo, "entirely, whole " and kainos, "new"). "The debate within geology is a long bureaucratic process with many internal disputes about scientifically justifiable evidence", Zalasiewicz[6] confides to us during the opening session in January. But what does it mean when a term from the Natural Sciences which has not even been established yet, is introduced in the public debate from the perspective of the humanities, social sciences and cultural studies? Will the idea of a human age lead to a flowering of artistic inspiration, like the images of dinosaurs have stimulated our imagination?

During the four-day opening at the HKW, the ethical, aesthetic, political, and economic dimensions of the Anthropocene were discussed. We will delve deeper into the Anthropocene from the perspective of justice, and look at the possible political consequences of a "human epoch", but first we will review a telling example of media's reception of this term. It was triggered by an interview published in Die ZEIT[7], with the geo-biologist and co-initiator of the project, Reinhold Leinfelder. As a response to the interview, a reader complained about the journalist's careless research, and of Leinfelder's incompetence, since they designate the chemistry Nobel laureate Paul Crutzen[8] as having coined the term. The reader quoted Wikipedia, where Antonio Stoppani is said to be the originator of the term. Two days later Die ZEIT published an explanation of the origin of the term[9]: while Crutzen referred to the Anthropocene as an epoch, Stoppani did as a whole era ("Anthropozoikum"). Leinfelder also responded to the criticism eleven days later with an even more detailed statement on his blog. Here he certified Crutzen as understanding the correct geo-chronological hierarchy level, and of seeing the great potential for a new epoch concept.[10]

What makes this example interesting is the "Open Access" to the debate around a scientific term. We are here allowed to follow and participate in the struggle over the right of definition, between scientists, journalists, Wikipedia authors and citizens. Today, renowned scientists take their time to justify their research to interested citizens. That would have been unconceivable a few decades ago. It questions the privilege of science as a self-referential "gate-keeper" of knowledge, standing above social responsibility. It is unclear, though, to which extent criticism in the media will actually change the scientific system and the power conditions around "recognized knowledge" in society.

Coming back to the previously mentioned subject of the political implications of the Anthropocene; this was presented under the "thematic Island Oikos" (altgr. oikos, eco- for ecology and economics, and equivalent of household). "What does the term Anthropocene mean for themes such as sustainability, resource management and good governance?" A lively discussion with participants from the social and cultural sciences [11] was started by Paulo Tavares. He introduced the example of the planned reform of the national forest policy [12] in Peru, a country in possession of a quarter of the planets tropical forests. In 1975, the Law on Forests and Wild Plants redefined the national forests. According to Tavares, the legal status of land was redefined so that the Amazon could turn to an “economically driven cartography”. The resistance of the new law addressed in particular "two decrees simplifying the sale of communal indigenous land – i.e. its privatization - and reclassification for agricultural use by investors"[13].

In this context, Christina von Braun recapitulated the history of the privatization of land since the 17th Century, as it was analyzed by the economic historian Karl Polanyi in The Great Transformation [14]. Since industrialization, landless people have only had their own labour to sell, what ultimately means their own body. Today, this is reflected very clearly in the "Biocapitalism" of the Anthropocene. The welfare state would ultimately only try to alleviate the consequences of industrialization. To stop this development, a new biopolitics would be needed, e.g. a charter for the protection of nature, to counteract the capitalist approach of "making nature better". The biopolitical discourse must be determined by humans becoming aware of just being “a species among other species". This would lead to an understanding of other species as entities with their own rights. As a consequence, the epistemic framework itself, which is defining life, has to be reconsidered.

Another exciting example of the reception of the "Anthropocene project" is the “Kreuzberger Salon” in Berlin, founded by Miriam Wiesel and Axel Schmidt in 2010. In its 23rd discussion on "The Entirely New", the participants reflected on the history of the commodification of nature and about the separation between culture and nature. Schmidt began the evening with a visual input. He ascribed our current conception of nature to the historical background of the industrial revolution and the enforcement of the idea of the free market. Due to the industrialization of agriculture, bourgeois interest grew to find new markets as they sought to sell the surplus of their production. The supposed “western progress” already at that time lead to diversity losses in plant life. The current degree of irrevocable loss of biodiversity could hardly have been envisioned at the beginning of industrialization, however. During the Salon discussion, Wiesel recalled Christina von Braun's contribution at the panel discussion earlier: the process of becoming aware of our connection to nature, which arose from man tilling the soil, is just taking place at the moment.

In respect to this, Schmidt quoted various passages from The Natural Contract, by Michel Serres [15]. Serres describes humans as parasites who plunder their host, the world, until having destroyed their own livelihood. "The parasite takes everything and gives nothing, and the host gives everything and takes nothing." [16] This attitude conforms to the ruling and ownership rights of an exclusively Social Contract, but must be supplemented by a "Natural Contract" with "rights of symbiosis": however much nature gives man, man must give that much back to nature, now a legal subject" [17]. As a legal person, nature is bestowed with the rights to vote and to have a say. The philosopher Akeel Bilgrami was mentioned in the Salon debate. He had expressed concern for how long it will probably take for nature to receive the right to vote, considering it took so many centuries for certain groups of people. In this context, it was noted critically that the needs of nature are not even known, and much less its possible modalities of exchange. In contrast, on the other hand, nature has developed quite sophisticated exchange systems that could perhaps inspire us to see beyond the mere cognitive exchange. For example, some trees have roots that are chemically in contact with each other, and send out ‘warnings’ when parasitical infestations threaten. Serres also asks what the reciprocity principle in the "rights of symbiosis" between man and nature could look like: "What do we give back, for example, to the objects of our science, from which we take knowledge? Whereas the farmer earlier in bygone days, give back, in the beauty that resulted from his stewardship, what he owed the earth??, from which his labor wrested some fruits. What should we give back to the world? What should we written down on the list of restitution?" [18].

Everybody taking part in the salon seemed to agree that something should be done about this, “because spaceship Earth just doesn’t have any emergency exit” [19]. Furthermore, as middle-class Europeans, we would all be victims and perpetrators at the same time. We can’t escape climate change and are therefore forced to be political, to guide strategic interests towards common goals. Regarding this, Dipesh Chakrabarty's view of history was brought to mind. Chakrabarty believes that the separation between natural history and human history will be dissolved by climate change. This should also be the opportunity for developing a new collectivism, because this is about the survival of the species. At the panel discussion, he had urged for the fight for common goods and justice to be continued - but from the perspective of humans being as parts of the whole and in constant exchange with nature.

At this point, we come back to the initial questions of the article: which parts of this discussion initiated within geology and so lively discussed at the HKW can we take with us in our everyday life? Firstly, the awareness that more and more open formats allows anyone interested to participate actively or tacitly in scientific research debates, as part of the development of a scientific concept. In a HKW panel discussion, for example, anyone in the audience can ask questions from an artistic or socio-ecological perspective. Anyone can publish their own perspective or knowledge as a comment in an online-newspaper. Overall, however, the four-day-opening of the Anthropocene Project, as a format designed by the HKW, seems not to reflect a "process of open participation". In fact, the format does not go beyond the level of involvement of a classical conference. Maybe consultation or participation beyond a level of just getting informed, one that would question the Anthropocene research process, was not actually desired.

Secondly, the Salon called attention to the need for new exchange formats that would allow the overwhelming amount of issues addressed during the opening of the Anthropocene Project to be digested in subsequent dialogues. The information flood of such a mammoth event can deter not only newcomers but also more experienced ‘citizen scientists’. Compensating this, it was possible to listen to all the talks and seminars again afterwards on the HKW website. Unfortunately, questions and comments from the audience were not recorded nor made available for later. A comment or tweeter online function for the panel discussions could have been one possible format allowing audience interaction.

A similar overabundance [20] of content as at the opening event in January characterised the first exhibition of the Anthropocene Project, inaugurated on April 25th and entitled: “The Whole Earth. California and the disappearance of the outside". It staged the Whole Earth Catalog, which was founded in 1968 by Stewart Brand and appeared regularly until 1972. This publication wanted to give tools and skills to the grassroots movements of its time. The intention was to address "the power of the individual, to conduct his own education, find his own inspiration, shape his own environment, and share his adventure with whoever is interested." [21] The curators at the opening described the limits of two 70s Californian utopias: the technophile computer culture, and the idealistic flower-power culture. Both cultures inspired each other. The curators talked about "how these horizontal limits of the American horizon would go on to develop into a global circular movement". With this they probably wanted to raise the question of how the American dream of progress has reflected on the worldwide environmental movement and other network cultures. Is this another attempt to present the Western perspective of the "Blue Planet" as a universal global movement? At least this is the impression one gets from the title of the catalogue, "Whole Earth Catalog", and the catalogue article entitled "We are as Gods" [22]. Moreover, the exhibition space did not manage to communicate the upbeat mood of the time. Also, the overabundance of reading led to the arduous feeling of being stuck in the middle of the "Whole Earth Catalog". Unfortunately, the text and illustration boards installed on trade show displays gave the exhibition design an even more fragmented and crowded appearance. After all, a choir was performing at the opening, and visitors visibly cheered along with songs of the 70s.

The question remains, what the idea of the Anthropocene can contribute to a future sustainable society. For this, the science historian Jürgen Renn suggested that a new research agenda be developed. This makes us curious, since the added social value of the Anthropocene hypothesis creates an arc of tension: it is, on the one hand, an anthropocentric vision of the world placing human action and its consequences at centre stage, and on the other hand, it claims to overcome the social narrative of separation between nature and culture, and to take responsibility for the social and political consequences of this historical narrative.

Without a doubt, the Anthropocene as a term is already being used by the scientific advisory policy bodies, as in a recently held speach by the Secretary General of the Scientific Advisory Council on Global Change WBGU, Dr. Inge Paulini, proves during the conference "Consequences of the Report of the German Bundestag's Study Commission Growth, Wellbeing, and Quality of Life"[23]. The Coming of the Age of the Anthropocene since the industrial revolution is changing the political field of action fundamentally, making "a transformation toward a climate-friendly and sustainable society very urgent." It will be exciting to see whether the thesis of the Anthropocene can fulfil this pioneering role or not.

↑ 5. Das Anthropozän-Projekt. Eine Eröffnung. Detailliertes Programmheft, S. 2 (Stand: 10.03.2013):

↑ 6. Im Gespräch (10.01.2013) mit Jan Zalasiewicz, Leiter der Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy.

↑7. Ulrich Schnabel. „Wir Weltgärtner. In dieser Woche wird in Berlin eine neue erdgeschichtliche Epoche eingeläutet: Das Anthropozän. Der Begriff soll unser Denken verändern. Ein Gespräch mit dem Geobiologen Reinhold Leinfelder.“ DIE ZEIT, 10.01.2013, Nr. 3. (Stand: 16.03.2013).

↑ 8. Paul J. Crutzen, Christian Schwägerl. "Living in the Anthropocene:

Toward a New Global Ethos." 24.01.2011. (Stand: 10.03.2013).

↑ 9. "Natürlich haben wir recherchiert. Der Begriff Anthropozän (Anthropocene) stammt tatsächlich von Paul Crutzen und wurde von Paul Crutzen und Eugene Stoermer (2000) in einem Newsletter publiziert. Anthropozän bezeichnet geochronologisch eine Epoche. Das erscheint plausibel. Stoppani, der übrigens von Crutzen, Leinfelder und anderen in vielen Arbeiten als Ideengeber erwähnt wird, sprach 1873 von der anthropozoischen Ära (was in Kurzform also das ,Anthropozoikum' wäre). Damit wäre die Menschenzeit dann aber gleich eine ganze geologische Ära geworden, auf einer Ebene mit dem Paläozoikum, Mesozoikum oder Känozoikum. Das wäre dann vermutlich doch etwas zuviel der Ehre des Einflusses des Menschen, denn ob die Menschenzeit wirklich, wie eben das Paläozoikum, Mesozoikum oder Känozoikum über 66 Millionen (Känozoikum), 190 Millionen (Mesozoikum) oder 290 Millionen Jahre (Paläozoikum) anhalten könnte, erscheint doch sehr fraglich. Die deutsche Wikipedia-Seite ist übrigens (mit Stand 12.1. 10 Uhr) diesbezüglich einfach falsch.“ Schnabel, op.cit.

↑10. „Erst Crutzen betonte die große Zweiteilung des (bisherigen) Holozäns in einen zwar regional vom Menschen beeinflussten Zeitraum (Holozän p.p.) und einen jüngsten Teil (ab ca. 1800), der global stark vom Menschen mitgeprägt wurde und wird, dem ,Anthropozän'. Damit hat er m.E. die richtige geochronologische Hierarchieebene gewählt und den tatsächlichen Unterschied zwischen beiden Einheiten herausgearbeitet. ,Anthropogene' wäre nur eine Umbenennung des bisherigen Quartärs. ,Anthropozoikum' würde dem Menschen eine unvorhersagbar hohe Bedeutung als erdsystem-dominante soziale Spezies geben, die über viele Zehner, wenn nicht gar Hunderte von Millionen Jahren anhalten würde, das wäre unrealistisch, außerdem würde die Untergrenze wiederum mit der Untergrenze des Quartärs zusammenfallen, der Begriff hätte also wiederum nur ,deklaratorischen' Charakter. ,Anthropozän' jedoch betont die wesentlichen Unterschiede zwischen der natürlichen globalen Umweltstabilität der nacheiszeitlichen Warmzeit, deren Zuverlässigkeit Grundlage für den Aufbau aller bisherigen gesellschaftlichen Nutzungsstrukturen (Ackerbau, Viehzucht, Städtebau, Handel mit Infrastrukturen) war, und des Anthropozäns, in der das Erdsystem global maßgeblich vom Menschen mitgestaltet wird.“

(…) „Es war Paul Crutzen, der das Potenzial des Begriffes Anthropozän / Anthropocene als neue känozoische Epoche tatsächlich erfasste. Eugene Stoermer ließ sich von ihm überzeugen und publizierte mit Paul Crutzen im Jahr 2000 den ersten formalisierten Vorschlag. Allerdings wurde erst in der Nature-Arbeit Paul Crutzens aus dem Jahr 2002 das Konzept zum ersten Mal geschärft. “Anthropozän - die Diskussion: Begriffsherkunft, Weltbild, Herausforderungen" Blogeintrag vom 21.01.2013. (Stand: 16.03.2013)

↑ 11. Diskussion mit Christina von Braun (Institut für Kulturwissenschaft, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin), Aldo Haesler (Département de sociologie, Université de Caen), Paulo Tavares (Department of Visual Cultures, Goldsmiths, University of London). Moderation: Doris Akrap (Redakteurin bei der tageszeitung).

↑ 12. Gesetz über die Forsten und die Wildpflanzen (Gesetz Nr. 21.147). Siehe auch: „Política Nacional Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre“, Ministerio de Agricultura. Propuesta preliminar, diciembre 2012. (Stand: 16.03.2013).

↑13. „Im peruanischen Amazonasgebiet verfügen indigene Gemeinschaften über zwölf Millionen Hektar an titulierten Landflächen. Hinzu kommen weitere Gebiete für so genannte territoriale und kommunale Reserven. Auch wenn es immer wieder Probleme mit dem Prozess der Vergabe von Landtiteln gab und gibt: Der zentrale Konfliktpunkt ist ein anderer. Die im Boden lagernden Rohstoffe wie Erdöl und Mineralerze und auch der Waldbestand und dessen Holzressourcen gehören per Verfassung dem peruanischen Staat. Erkundung und Abbau dieser Rohstoffe sollen in erster Linie transnationale Konzerne leisten. Der Staat vergibt dafür Konzessionen. Diese überlagern jedoch zu einem großen Teil das titulierte Landeigentum und die Territorien indigener Völker und Gemeinschaften.“ Link: http://www.lateinamerikanachrichten.de/index.php?/artikel/3846.html (Stand: 16.03.2013).

↑ 14. Karl, Polanyi. „The Great Transformation. Politische und ökonomische Ursprünge von Gesellschaften und Wirtschaftssystemen“, übersetzt von Heinrich Jelinek. Europaverlag, Wien 1977.

↑ 15. Michel Serres, Le contrat naturel. Paris, Bourin (dt. Ausg.: Der Naturvertrag. Frankfurt/M., Suhrkamp, 1994).

↑ 16. Michel Serres, op.cit., S. 69.

↑ 17. ebenda.

↑ 18. ebenda.

↑ 19. „Das Raumschiff Erde hat keinen Notausgang. Energie und Politik im Anthropozän.“ Paul J. Crutzen, Mike Davis, Michael D. Mstrandrea, Peter Sloterdijk u. a., Suhrkamp Verlag, Edition Unseld, 2011.

↑ 20. Mit Arbeiten von Ant Farm, Eleanor Antin, Martin Beck, Erik Bulatov, Angela Bulloch, Öyvind Fahlström, Jack Goldstein, Nancy Holt und Robert Smithson, Philipp Lachenmann, David Lamelas, Sharon Lockhart, Adrian Piper, Robert Rauschenberg, Josef Strau, Suzanne Treister, Bruce Yonemoto und anderen.

↑21. "We are as gods and might as well get good at it. So far remotely done power and glory - as via government, big business, formal education, church - has succeeded to the point where the gross defects obscure actual gain. In response to this dilemma and to these gains a realm of intimate, person power is developing - power of the individual to conduct his own education, find his own inspiration, shape his own environment, and share his adventure with whoever is interested. Tools that aid this process are sought and promoted by the WHOLE EARTH CATALOG." How it worked , (Stand: 26.04.2013)

↑ 22. Founder Stewart Brand, in his 1968 CATALOG article, "We are as gods" said, "At a time when the New Left was calling for grass-roots political (i.e., referred) power, Whole Earth eschewed politics and pushed grassroots direct power—tools and skills. At a time when New Age hippies were deploring the intellectual world of arid abstractions, Whole Earth pushed science, intellectual endeavor, and new technology as well as old. As a result, when the most empowering tool of the century came along—personal computers (resisted by the New Left and despised by the New Age)—Whole Earth was in the thick of the development from the beginning." (Stand 26.04.2013)

↑23. Tagung des DNR zu den „Konsequenzen aus dem Bericht der Enquete-Kommission Wachstum, Wohlstand, Lebensqualität. Ein Vorbild für Europa?“ in der Vertretung der EU-Kommission, Berlin, 24. April 2013.

|